Results for ""

Stanford researchers have created "unimals" (short for universal animals that are digital) to help Artificial Intelligence (AI) researchers study and develop more general purpose machine intelligence.

Agrim Gupta of Stanford University, Fei-Fei Li, co-director of the Stanford Institute for Human-Centered AI and co-creator of ImageNet, along with other colleagues observed these unimals to explore how intelligence is tied to the way bodies are laid out, and how abilities can be developed through evolution as well as learned.

If researchers want to re-create intelligence in machines, they might be missing something, says Gupta. Biological intelligence is the combined effort of mind and body working together. However, AI only focuses on the mind's capabilities to build machines to perform tasks that mostly can be done without using a body such as natural language processing, image processing, playing video games.

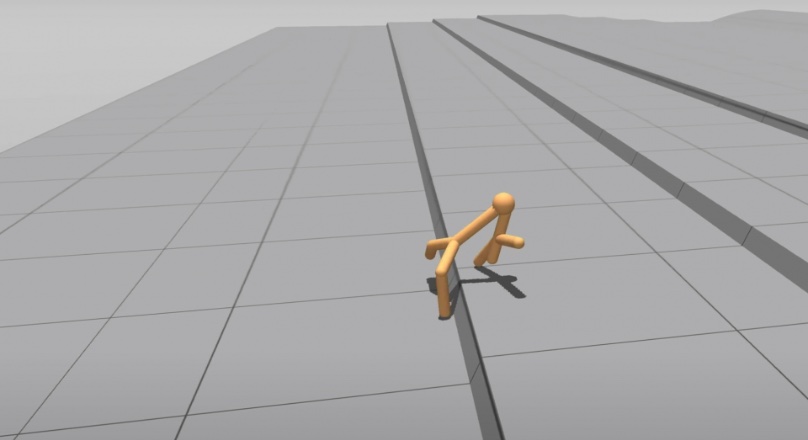

However, with unimals that precedence is set to be broken as scientists are exploring how robotic bodies can adapt and develop to perform specific tasks and accomplish at new skills. The unimals have one head and several limbs that are trained by a technique called deep evolutionary reinforcement learning (DERL), which the Stanford team specifically developed for them. The DERL helped unimals undergo reinforcement learning to complete virtual tasks such as walking across different types of terrain or moving an object. The unimals that accomplish these tasks the best are then selected and are introduced to mutations.

These mutated "offspring" perform the same tasks, and are further introduced to mutations hundreds to times to evolve and learn. There's a vast number of mutations to evolve to; such as addition of limbs, changing flexibility or length of limbs, etc. Through these experiments, unique unimals have been produced - some unimals have evolved to move across flat terrain by falling forwards; some evolved a lizard-like waddle; others evolved pincers to grip a box.

Further, the scientists introduces them to previously unknown tasks to test their general intelligence. Those that had evolved in more complex environments, containing obstacles or uneven terrain, were faster at learning new skills, such as rolling a ball instead of pushing a box. They also found that DERL selected body plans that learned faster, even though there was no selective pressure to do so. “I find this exciting because it shows how deeply body shape and intelligence are connected,” says Gupta.

Ultimately, this technique could reverse the way we think of building physical robots, says Gupta. Instead of creating the body and 'mind' if a robot to perform specific tasks, DERL can help develop an optimal body plan, evolve an AI and then build them into machines.

For Gupta, free-form exploration will be key for the next generation of AIs. “We need truly open-ended environments to create intelligent agents,” he says.